From Woolworths to W.H. Smith (alias TG Jones): what is the future of the British High Street?

With the cost of living crisis seemingly becoming a cost of living lifestyle, and businesses shutting down at an exponential rate, what does the future look like for the High Streets of the UK?

Let’s kick this week’s newsletter off with a short quiz.

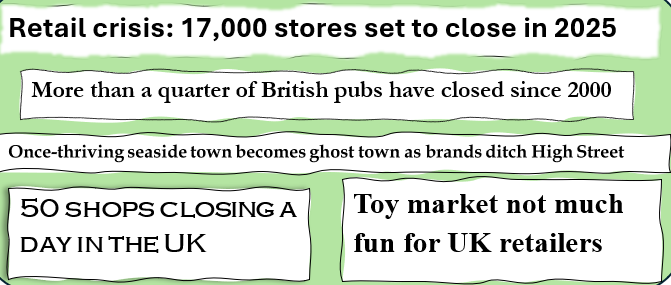

Below, there are five headlines — four true, one fake. Which one do you think is the real one?

Is it the one about 17,000 stores set to close throughout this year? That’s a lot of shops!

Perhaps it’s the humorous ‘not much fun’ pun with ‘toy market’ headline - after all, surely toys are a consistently promising business?

Or the ‘once-thriving’ seaside towns? Surely with the beaches being as pretty as they are, the shops are full of inquisitive tourists?

Nope. Not that one either. In fact, all of them are real.

This is only the beginning. There are endless articles that we can find online illustrating the visibility - or lack thereof - of High Streets within the UK.

The beginning of the demise began, arguably, with one of two situations:

a) the shutting down of major shops like Woolworths and Blockbuster in the mid-late 00s.

b) the increase in products that were (and are) able to be bought online, cheaply and quickly

Generally, we can probably suggest that most would argue it’s a combination of the two. As major shops shut down for a multitude of reasons, and especially so when they’re companies where people know what they’re visiting them for, it only stands to reason that consumers then try to find the same deal elsewhere (as they know it exists). The internet then becomes a good place to look, where enterprises like Amazon reign above all in the shopping department, and more recently TEMU - which is its own particular concept and issue. Even separately, take a handful of other aspects - the gig economy giants such as Deliveroo and Just Eat; social media and online transactional selling through places like Shopify, Vinted, eBay, even Facebook Marketplace; the numbers of people working from home (although this seems to slowly be diminishing); the options for supermarket deliveries; the number of forms of entertainment, media, and other ‘watchable’ things now being available through streaming services, collaborative technologies, and increasingly popular subscription-based models; people opting (or in many cases *requiring*) a minimalist lifestyle approach and being less prone to just buying things on a whim… the list of possible ways of buying and selling that doesn’t even mean you have to leave the sofa allows the pavements of the High Streets to barely even be scuffed, let alone dented. All of these elements (and plenty more that I have not outlined, as well as some I’m probably not even remotely aware of) have collaboratively made it less necessary, or in fact even pointless, for many to need to go out and about to spend money. I should add a quick note that a handful of shops have actively gone against the propensity for online shopping. Primark is possibly the best known example -a cheap fashion retailer, which is perfect for the “run in and grab” situation, and doesn’t sell online. At all.

In 2025 especially, hikes in tax payments and wage-based expenses, including a damning combination of higher National Insurance contributions to be applied to lower thresholds of pay against a raised minimum wage (i.e. the National Living Wage (minimum wage for people over 21) is now £12.21, which is a welcome increase, but a decrease of around £4,000 per year in the soc-called Secondary Threshold at which NI contributions should be made by the employer, which has risen from 13.5% to 15% on earnings above £175 per week (and that itself drops to an astoundingly small £96 per week across the 2025-26 period). Phew. It goes some way to explaining why work periods and contracts are so immensely fragile in many instances, and further why many of the smaller firms appear to be increasingly hesitant to employ people; a slightly difficult or less successful month could be all it takes for a small business to find themselves in turmoil.

Of course, shops like Poundland, 99p Stores, B&M and Home Bargains have functioned tremendously well as cheap-ish places to shop (remember the near riots when Poundland had to raise prices from everything being £1?), and generally continue to do so to this day. Poundland, somewhat astonishingly, is going through the motions currently, as the 741-strong company sees evolutionary collapses across the board after being acquired by the Gordon brothers in June of this year. Many towns (my hometown being a particularly strong example) have had local people open discount stores or places actively designed to allow people to buy things more cheaply — but as a result of rent costs, employer costs, or even just the general footfall not being as high as expected, these places then have to shut down, and it becomes a vicious circle. Give me a minute and I can list 5, maybe even 10, businesses which have opened and shut down within a year. Both small, local attempts, and major conglomerates.

So where is it all going wrong? Surely we can’t just blame the Internet on it all - and with what’s going on internationally and technologically, could this even be the beginning to a reversal in shopping styles? (I have quite the theory that we will soon reach a point where there is so much ‘Internet’ that people actively tries to go away from it and it becomes as much a nostalgic thing of the past as, well, Blockbuster and Tamagotchis).

55 minutes prior to writing this line, an MSN article was published that states the following:

High Street bosses warned firms are being ‘taxed out’ as jobs in the retail sector hit a record low.

Retailers sounded the alarm after figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealed there were 2.78m jobs in the industry in June – down 97,000 on a year earlier. Nearly 400,000 retail jobs have been lost in the past decade.

Despite the difficulties that have been faced greatly over the last few years, it looks to be that it could only compound more and more. A few research articles on the subject point towards some interesting findings, both quantitatively and qualitatively. All the way back in 1988, John A. Dawson writes in The Geographical Journal about a “conscious design of total shop appearance”:

“Large companies now operate through several different formats on the same High Street, for example the Burton Group operates Principles, Top Shop, Evans and Dorothy Perkins for women and a further four formats for men. Other groups (Next, Sears etc.) similarly operate a range of formats each targeted at a specific consumer group. Not only product is involved but also shop location, layout, interior design, external appearance, employee training—a total designed package is put together (Eastbury, 1986).”

Quite humorously, it also describes Woolworth as “returning to being a High Street force of a different kind”. Gotta love contemporary academia.

With a focus on London, Goevert and Towle (2020) remark on previous work of Jones, Roberts and Morris (2007), outlining that some of the things that has led to the historic success of London’s retail areas include them being “key components in the strategic transport network” (Edinburgh is another great example of this, even if Princes Street gets far too congested far too easily, as well as Birmingham, Manchester and Cardiff, for instance), “pseudo-estuaries that channel movement from the surrounding catchment of, typically, residential streets” (check out Bath, Southampton and Glasgow as similar examples here), “locations for a wide range of on-street facilities and services, such as kiosks, cash points, telephone boxes, public art, parking, etc.” (which I’d say is just as intrinsic to High Streets in towns as well as in the big cities, where I point you towards places like Havant, Gateshead, Caerphilly, and Livingstone (although that entire place is basically a massive shopping centre), and “centres of local identity, often peppered with landmark features that give them a distinctive/historic appearance” (which I’d say is visible in cities including Portsmouth and Plymouth with their strong, proud maritime history and culture, Chichester with its Roman walls, Bristol with its openness to public art and slightly ‘alternative’ culture, and Liverpool’s pride of being, well, Liverpool).

So whilst there are a lot of identifiable elements of High Street areas that can and/or do make them successful, or at the very least, ‘positive’ locations for retail and investment, it seems that the decline is happening on an unprecedented level. If we are to look at the examples above, we can probably think quite easily and clearly about locations which lack one, two, or all of those things. For many towns and villages, their transport network is irregular, expensive or unsystematic (and don’t get me started on the extortionate, complex, and solely technology-based costs of parking that have in many places been monopolised by one or two companies - oh, Brighton), their town lacks character and investment in its local identity, and street furniture and facilities like CCTV, cash points, benches and bins are either broken, decrepit, or non-existent.

All of these might seem like problems that can have money thrown at them and it might fix a few things, but it’s not a long term solution. Goevert and Towle actually mention the 27 Portas Pilots that tried to become a thing back in 2011 - “a populist response to a deep-seated structural problem”.

I think this is where so much of the problem has befallen High Streets more and more. Areas where the sectors and industry has developed over the last many decades, and had the necessary investment, have seen growth, but the areas without it are so many and so great that the decline has to be managed far more regionally, and far more consciously. Applying one-size-fits-all approaches just doesn’t work, and a more localised approach that takes into account the needs of the local people (which are wildly different from place to place, again as an intrinsic facet of how the country is built) will slowly, but surely, start to see developments taking place bit by bit.

It’s all been going very, very wrong over the last few years. It’s not going to improve overnight, but over many days and nights, with a lot of sustained investment - not money thrown willy-nilly at the struggling areas - we might see some sort of change coming.

Are High Streets still a place where retail is the focus? Should management strategies be changing? Can we just alter taxes and investment into different areas or do we need a more steadfast approach? What do we want the future of our towns and cities to be?

These are all the questions we should be asking, but I think we already have many of the answers.

What do you think? Have you got any strong opinions about the modern High Streets and shopping sectors? Please feel free to share them!

References:

Dawson, J. A. (1988). Futures for the High Street. The Geographical Journal. 154(1). Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/633470

Goevert, T., & Towle, A. (2020). 3 High street places: doing a lot with a little. Design for London: Experiments in urban thinking. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv13xps62.11

Jones, P., Roberts, M., & Morris, L. (2007). Rediscovering mixed-use streets. The contribution of local high streets to sustainable communities.